Handle with Care: an interview with Louisa Reid

Handle with Care, Louise Reid’s latest YA novel, introduces us to best friends Ashley and Ruby. In the dramatic opening scenes, Ruby – whose sections are written in verse – goes into labour during a history class with a baby she didn’t know she was having. The book examines issues of mental health, friendship, family and responsibility, while deeply engaging the reader with the situations of the girls and the people around them. It’s both brilliantly plotted – I was desperate to see how events would unfold – and profoundly moving.

When Louisa and I spoke and I confessed to sobbing as I read, she told me that writing it was an emotional experience, too: “It took me a while to finish this book. I started writing it a while ago, then I stopped because I could see where the story wanted to go. I wasn’t sure if it was a direction I would be allowed to go in, or if my readership would find it too much. But in the end, that was what the story demanded. Things don’t always turn out the way they should in real life, and I feel like my readers know that. We need to acknowledge that mistakes are made, and that there are victims and there are consequences. It would have been going against my every instinct to tie the story up in a neat happy ending, although there is hope there, too.”

I asked whether Louisa felt there was a pressure on writers of YA and children’s fiction to shy away from darker themes. She cites The Bunker Diary by Kevin Brooks as an inspiration. “It has stayed with me throughout my writing career as something I wish I had written. It is so bleak, and so good. I was shaken to the core – I couldn’t believe he ended it the way he did. I also think we like a weepy – sometimes you have to let your reader have a good cry.”

Both teenagers undergo seismic changes through the book. For Louisa, it’s important to depict young people whose perspective is shifting from accepting the worldview of parents and other authority figures to developing their own moral compass. Ash has always idolised her kind and capable mother, but during the novel she begins to question some of her actions and motivations. “The moment when you realise your parents are real people who don’t have the answers to everything can be a foundation shaking experience.”

Louisa drew on her experience of both raising and teaching teenage girls, but says that part of the authenticity of the characters’ voices comes from drawing on her own memories of adolescence. “So much happens within a short period of time, and it’s so fundamental that it does still feel vivid to me. The mistakes you made, the good times, the bad times, the friendships, the heartaches, the fears. When I was a teenager, the idea of getting pregnant was the ultimate spectre. Nowadays, I hope there's less of a stigma around teen pregnancy, but I think it's still very, very hard for young women who have to face not only the facts of a baby when they're still babies themselves, but also the way in which the world reacts and responds.”

Digital gossip and the distorting lens of social media torment both Ruby and Ash and – as someone who grew up in a pre-digital age – I found these elements both utterly believable and deeply distressing. “It's an online life, now. The way things can spread and proliferate can be really frightening, and I think most young people live with a fear of someone saying something about them online, or some picture being shared and the consequences of that. Part of the reason Ruby's so lonely in the book is because she feels attacked in this online world as well as in person, so she shrinks in on herself and feels cut off from all those social connections you really need as a young person. That loneliness is a driving factor in her feeling depressed and fearful and isolated.”

In the digital age, gossip and drama – which we all remember being central to our teenage lives – is turbocharged. “You can't control where that picture goes, where that video goes, how that lie develops and spreads. People are poisoned against a vulnerable individual who needs love, kindness, patience, but instead gets sneers and mockery. The boys at school making crude comments… it's completely inappropriate, but this behaviour is normal.” The book also makes sharp and wise observations on the chasm between the glossy cuteness of parenting a newborn as viewed on Instagram and the exhausting reality.

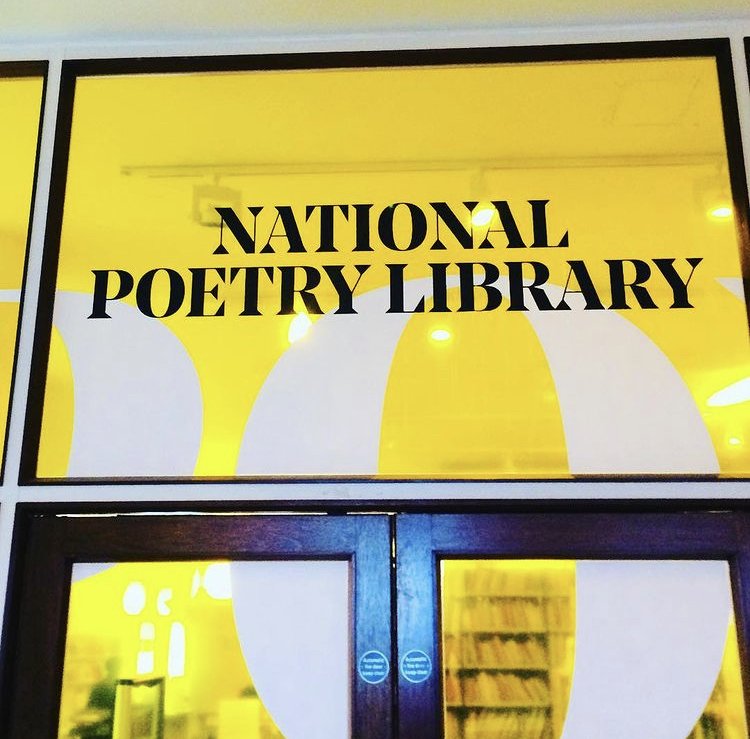

I wondered whether the hard-hitting nature of some of themes Louisa depicts had led to any resistance from gatekeepers, but she has found teachers and school librarians hugely supportive. “They are more than willing to get books that tackle quite complex and perhaps heart-wrenching stories into the hands of readers who will respond to them. There's a place for everything in a school library: the lighthearted comic stuff, the graphic novel, the classics. There’s always that magic of: right book, right time, right reader. Sometimes you need a book that allows you to experience the problems of somebody else to help you work through your own. It's about building empathy amongst your readership for people who are suffering or feel on the outskirts.”

The idea of empathy is threaded into the structure of Handle with Care, as the voices of the two girls – and the different perspectives they have on the unfolding action – carry the narrative. Louisa says, “We need to allow ourselves to see things from multiple perspectives if we're ever going to work together, to be kinder to each other.”

“I’d love readers of this book to take away something of the importance of friendship, which all teenagers know already, but about being prepared to ask hard questions and listen to answers, even if they're unpalatable. Ash experiences how hard it is sometimes to keep going with somebody when they're pushing you away, but a message from the book is that although they may be telling you they don’t want to talk, perhaps they just can't express how hard life has become for them. In Ruby, that shows up in rage a lot of the time, and Ash doesn't fully understand that under the fury is this huge pain.”

The book also explores the idea of affluent neglect. Ruby wants for nothing in material terms, but her high-flying mother is emotionally distant, wanting to sweep her pregnancy under the carpet. “There’s a message for the adults reading too, actually, that with teenagers, they're not ready to deal with grown up stuff on their own. They need support, even when they're slamming the door on you. And it's so difficult to deal with emotional crises in young people. I mean, parents aren’t trained for that, are they? There's no manual.”

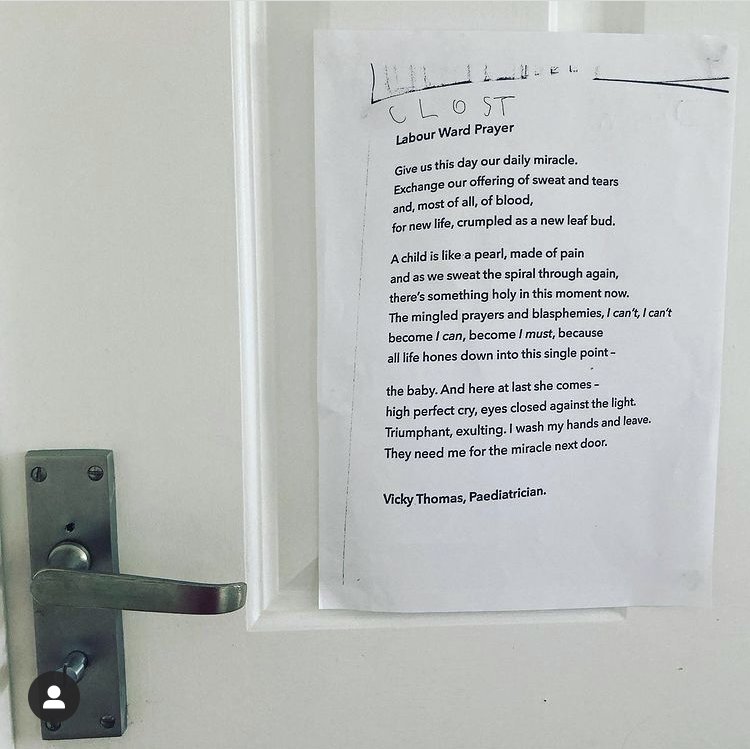

I asked Louisa about the decision to write the sections narrated by Ruby in verse. “The form is brilliant for getting to the heart of that subjective emotional experience. Initially, all the narrative was in prose but an early reader – and then my agent – both suggested I try this. Ruby’s sections are painful, and it gives them a real immediacy. It worked for her.”

Handle with Care is that very special thing: a propulsive page-turner that packs a real emotional punch, and a book that will open up hard and desperately necessary conversations. Ruby and Ash, and their powerful story, will stay with readers long after they turn the last page.

Handle With Care by Louisa Reid is out now.

This interview was commissioned for Books for Keeps Magazine.