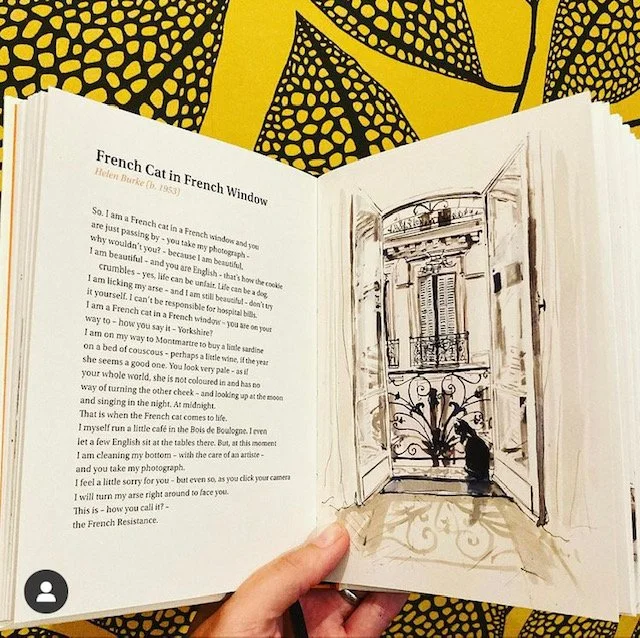

In Praise of Cats: The Book of Cat Poems

‘The smallest feline is a masterpiece’, said Leonardo da Vinci – a man who knew a thing or two about masterpieces. From the leaping kitten, sporting with leaves or twitching in gorgeous sleep, to the elegant elderly feline reposing severely before the fire in your favourite – now claw-raked – chair, we can never be said to ‘own’ a cat. They merely consent to share our lives, always archly aware that they are doing us a terrific favour.

This is not to say that our cats do not return our affection. Far from it. People who have never lived with a cat often criticise them for being cold or aloof. Only the cat lover can understand the deep, quiet pleasures of this relationship. “What greater gift,” asked Charles Dickens, “than the love of a cat?” Cats are capricious. Cats are choosy. Your interactions with them will be, always and exclusively, on their terms. So when your lap is full of stretched and purring peace – when cats relax, they show us all how it should be done – you are sensible of the great honour. And woe betide you if you wriggle.

Cats talk to us. There are commands, like the urgent bleat informing you, their reluctant butler, that their stately progress has been impeded by a door. Every cat I have ever known has been excellent at expressing disapproval. An irritable twitch of the tail leaves you in no doubt when you have affronted them, and if cats had eyebrows (do cats have eyebrows?) it’s easy to imagine that one would be perpetually arched. But there are also love songs, eloquent in purr and nuzzle. There is the beseeching pat and the satisfied exhalation as, having been round and about and arranged you to their satisfaction, they sink down onto a friendly lap.

As I edited The Book of Cat Poems, I met cats of every stripe (and striped cats too!) Here are hymns to the malevolent bruising Tom who haunts the city alleys, swishing and wailing and mauling his wicked way through the dark hours. A cat is only ever a half-tame thing, a whisker away from the tiger. The cat who basks and dozes on the rug all day might live quite another life at night, tripping the light fantastic over the rooftops of town or prowling for prey along country lanes.

No wonder the cat is so often seen as an uncanny creature, ‘strange, so strange’, as W H Davies has it. From the sphinx of Baudelaire and Oscar Wilde to the well-worn image of the witch’s familiar, any cat lover knows full well that a little magic lives in their pet.

“In ancient times cats were worshipped as gods,” wrote Terry Pratchett.

“They have not forgotten this.”

While kittens delight us with their frisking, grown cats can be gracefulness incarnate. Whorled into a perfect circle to sleep, stalking along high fences or simply delicately washing their ears, they move with the kind of languid poise we lumpen humans can only admire. Even hunting – eyes enormous, tail thrashing, bottom wiggling – they are ruthlessly elegant.

Poets have devoted many verses to expressing the particular balletic charms of a cat’s movements. Amy Lowell’s ‘Winky’ – such an undignified name! – immortalises her cat’s ‘glossiness of beautiful curves’ as well as articulating its maddening, demanding but adored personality. Christopher Smart, incarcerated in an asylum with only his cat Jeoffrey for company, conjured the animal’s movements evocatively: the rolling and washing, the claw sharpening, the stretching and the rubbing against things.

Some of the world’s greatest writers have dedicated themselves to the conundrum of describing a cat’s eyes. Swinburne writes of ‘Glorious eyes that smile and burn’, and Yeats of Minnaloushe, dancing in the night with his moon-filled eyes always changing. Harold Monro’s little black cat gives a hard stare to request a saucer of milk. Anyone who has been glowered at by a cat will recognise this stern and disapproving glare, an accusatory reminder that the bowl is empty and the hour late.

I love the poems I found about the contrary nature of cats. I have never met one that didn’t find itself, like the Rum Tum Tugger, on the wrong side of every door. Your knitting will be shredded, your newspaper sprawled upon as you attempt to read it, your slumber disturbed at a ridiculous hour by an enquiring, patting paw and your dinner stolen, quite brazenly and without compunction. Cats are exasperating. Nobody who loves them could pretend otherwise. We wouldn’t have them any other way.

Happiness is a warm cat, purring in your lap, warming your feet, and – of course – nipping your toes if you have the temerity to move. Cats love to be admired, accepting all devotion – including that of some of history’s finest poets – as no more than they deserve. I guarantee that your cat will be positively delighted if you settle down to read these poems in praise of felines on a long, dark evening – as long as you don’t get up again in a hurry.

The Book of Cat Poems was obviously a joy to edit and is beautifully illustrated by Sarah Maycock.