Poems for Christmas

For me, the greatest gift of the Christmas season is time to read. The offices and schools are closed. This year, pubs, restaurants, shops and cinemas will be off the menu for many, too. The weather is often appalling. The nights are long and dark and seem designed expressly for the purpose of snuggling under a blanket on the sofa with the tree lights twinkling, a glass of something tempting within easy reach and a great big pile of delicious-smelling, beautiful new books. Here are some of my poetic festive favourites – all would make great gifts, too.

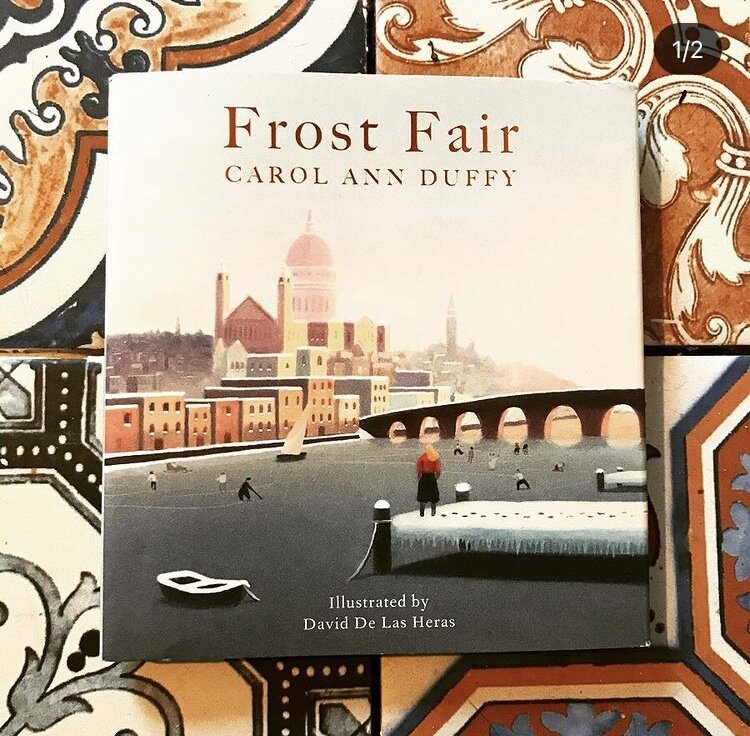

Carol Ann Duffy’s Frost Fair is completely wonderful, and makes me hanker after a re-read of Woolf’s Orlando. It’s so beautifully illustrated by David De Las Heras, it would make a lovely stocking filler.

Never has the exhilaration of whirling about on ice-skates been better captured than by Wordsworth, in a breathless and beautiful section of ‘The Prelude’ which I included in my second anthology, Tyger Tyger Burning Bright. I speak as a clumsy person, whose few attempts at skating have resulted in the kind of falls that elicit audible gasps from witnesses and some truly spectacular bruising. If Wordsworth can fill me with the desire to sail across frozen lakes under a wide wintry night sky, he can inspire anyone.

‘The Journey of the Magi’ by T S Eliot has an eerie, cold magic to it, perfect for reading and chewing over on a bitter winter’s night.

I love Betjeman’s ‘Christmas’ - hear the man himself read it here, with its evocation of the pull of family even more poignant this oddest of years (‘And girls in slacks remember Dad, / And oafish louts remember Mum’) and the seasonal cheer infecting everyone everywhere – from ‘provincial public houses’ to ‘many-steepled London’. I want to be in that country pub and on those glittering city streets for Christmas 2021.

Thomas Hardy’s gorgeous ‘The Fallow Deer at the Empty House’ is a favourite.

And Hardy’s ‘The Oxen’ perfectly captures how some scrap of childhood magic can cling to Christmas Eve and the vision of the nativity no matter what age and how agnostic I am.

Christmas Eve, and twelve of the clock.

“Now they are all on their knees,”

An elder said as we sat in a flock

By the embers in hearthside ease.

We pictured the meek mild creatures where

They dwelt in their strawy pen,

Nor did it occur to one of us there

To doubt they were kneeling then.

So fair a fancy few would weave

In these years! Yet, I feel,

If someone said on Christmas Eve,

“Come; see the oxen kneel,

“In the lonely barton by yonder coomb

Our childhood used to know,”

I should go with him in the gloom,

Hoping it might be so.

A contemporary poem I love is one for the festive refuseniks: ‘Bah… Humbug’ by Gregory Woods. This year, there will be lots of people perhaps missing the jolly chaos of a family Christmas, but this poems is a hymn to the allure of a solitary, batteries-not-included celebration with ‘books to the left of you, / gin to the right’. This poem was included in Christmas Crackers, one of Candlestick Press’s lovely pamphlets designed to be sent instead of a greetings card – perfect if you’d like to say something more substantial than ‘Season’s greetings’.

I bought a beautiful edition of ‘The Night Before Christmas’ a few years ago with Niroot Puttapipat’s beautiful silhouette illustrations and am frankly delighted that the kids insist on hearing it all year round. Due to our – frequently unseasonal – repeated readings, I am now word perfect. This confers an additional advantage: I can name all the reindeer (and, no, Rudolf doesn’t feature) and am therefore a splendid addition to any Christmas pub quiz team. Moore was a slightly unlikely Christmas poet, being an academic whose other works were heavy tomes on Hebrew. Legend has it that he composed this, his only famous poem, to entertain his children during a sleigh ride through Greenwich Village on Christmas Eve 1822, basing jolly St Nicholas on their coachman. I hope it’s true.

Also for children (though not only for children), I recommend the excellent selection of Christmas Poems edited by Gaby Morgan (who I’m lucky enough to have as editor for my Macmillan anthologies) and illustrated by Axel Scheffler of Gruffalo fame. And The Night Before Christmas in Wonderland by Carys Bexington, beautifully illustrated by Kate Hindley, was a new favourite last year with great verse, glorious pictures and clever homages to both beloved texts.

It’s not poetry, but I have to mention A Child’s Christmas in Wales by Dylan Thomas, which I try and read every year. And this year I have put Carol Ann Duffy’s new collection of Christmas poems on my wishlist.

Whatever you do at Christmas and wherever you are, I wish you happy reading. May your stocking be full of books and your cheeseboard always groaning.

Please note that this website contains affiliate links and I may earn a small commission (at no cost to you) when you buy through these links.